Mohsen Jaafarnia (2015). Iran and China Relationship: Product design based on cultural needs. New Silk Road Program 2015, GCIDC2015 Conference Proceedings, 2015世界华人设计论坛会议论文, 收稿日期:2015年7月30日 3rd - 10th July, Changsha, China. The People Museum Journal , Volume 1, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

Iran and China Relationship: Product design based on cultural needs

Mohsen Jaafarnia

Assistant Professor, School of Design, Hunan University,

China

An overview of the history between China and Iran shows that frequent exchanges of culture, religion, trade, art, science and technology are the distinctive features of their bilateral relations. Here we have traced the historical perspective that influenced the development of aesthetics of product in both Persian and Chinese culture. We have realized that the Persian products were exported to China in period of Sasanian and later the Changsha wares and northern and southern wares with same design of Sasanian were imported in Abbasid Dynasty. They include considerations involving visual elements and their inter-relations.

This paper is going to deeply search travelling of product design between Persia and China, hence shipwreck (named Black Stone) in the sea area of Indonesia was discovered, and there were about 60,000 of well-preserved products which more than 80 percent of them were from Changsha kiln ceramic products, since these products on the ship were obviously produced for the Persia in light of their exotic design styles. We have collected related 100 pictures of product belong to the sunken ship to show the experts who are working in the field of archeology in Iran.

The result has shown the contribution of Persian and Chinese designers to a wide range of art, design and commerce disciplines are often overlooked. This paper provides a glimpse of the rich cultural heritage within the Persians and the significant role that Chinese have played in the advancement of product design.

Key words: Changsha Kiln, Sasanian, Tang dynasty, Persia, China.

1. Introduction

Relations between Iran and China refer to the historic trade and cultural relation via the land and Sea Silk Road dating back to ancient times, which could help each other in different aspects such as product design.

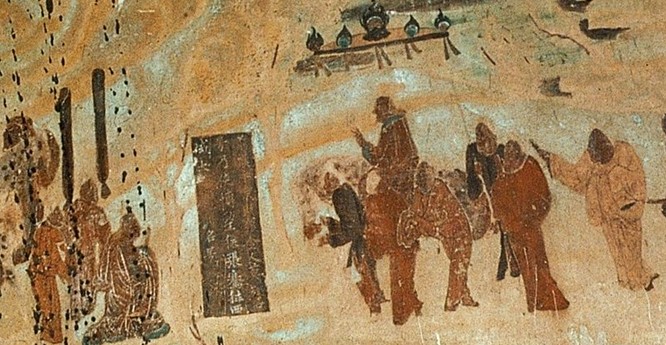

With an overview in the past, the Parthians and Sasanians had good contacts with China. The Chinese explorer Zhang Qian, who visited the west neighboring countries of the Han Dynasty in 126 B.C., made the first known Chinese report on Parthia. In his accounts Parthia is named “Ānxī” (安息), a transliteration of “Arsacid”, the name of the Parthian dynasty. Zhang Qian clearly identifies Parthia as an advanced urban civilization, "Anxi is situated several thousand li west of the region of the GreatYuezhi (in Transoxonia). The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. They have walled cities like the people of Dayuan (Ferghana), the region contains several hundred cities of various sizes. The coins of the country are made of silver and bear the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor. The people keep records by writing on horizontal strips of leather. To the west lies Tiaozi (Mesopotamia) and to the north Yancai and Lixuan (Hyrcania)." (trans. of Shiji) [1].

Figure 1. The travels of Zhang Qian to the West, Mogao Caves, 138 - 126 B.C. Wall painting.

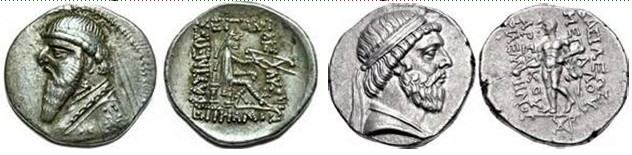

Figure 2. Coins of Parthian dynasty

Following Zhang Qian’s embassy and report, commercial relations between China, Central Asia, and Parthia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent via the Silk Road throughout the 1st century BC [2 & 3].

In another case we see, Can Kien, a Chinese general sent out by Wuto Fargana, Sogdiana and Bactria “astounded his countrymen by his accounts of the Persian civilization and products which he brought back from Persia. The Chinese, although great artists themselves or because of it were fascinated by the Persian art”. The famous Chinese traveler, Huan Tsang, to whom reference has already been made, reported that: “all they (the Persians) make the neighboring countries value very much.” [4 in 5].

Like their predecessors the Parthians, the Sasanian Empire maintained active foreign relations with China, Commercially, land and maritime trade with China was important to both the Sasanian and the Chinese empires. A large number of Sasanian coins have been found in southern China, confirming maritime trade. On various occasions, Sasanian kings sent their most talented Persian musicians to the Chinese imperial court [6]. Both empires benefited from trade along the land and maritime Silk Road, and shared a common interest in preserving and protecting trade.

At different times, under the Arsacids and Sasanian, a variety of Persian seeds, plants, mineral and industrial products went to China such as grape-wine and the art of making wine (Shirazian wine has recorded patent as a Persian special wine nowadays which is belong to Persepolis) [7 in 5], the “genuine brass” (copper and zinc), high grade steel described by the Chinese as “so hard and sharp that it can cut metal and hard stone” and is wrought in sharp swords, turquoise etc.

On the opposite direction porcelain, some copper alloys and the most important of all, silk were imported by Persian from China [8 in 5]. In these collaborations we can see many cultural exchanges and influences on the art of both sides. For example, Shah Abbas the Great in period of Safavid dynasty had hundreds of Chinese artisans in his capital Esfahan and Safavid Iranian art was also influenced by Chinese art to some extent [3].

In this case we can mention to series of evidence which proof relation of these two countries and development of product design.

Figure 3. A design inspired by the Sasanian models on a Japanese brocade, 8th cent. A.D.

Figure 4. Left, Sung Dynasty Silk Brocade. Right, Tang Dynasty 8th century. Shōsōin, Nara.

Figure 5, Left, Sasanian plate, with Shapure II (King) 4th Cent. A.D. Right, Sasanian silks

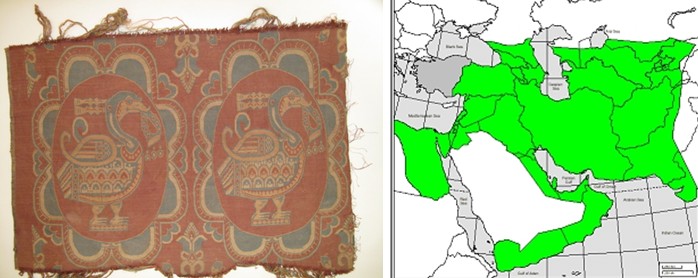

The brocade design “Hunting Lions" (Figure 3 and 4) is historical evidence of the cultural dissemination between the Sasanian Dynasty of Persia and the East during ancient times, in which the culture of the Sasanian Dynasty had gone to the East, via the "Silk Road". For this reason, this brocade pattern is of great significance. In these artworks we see, the hunting scenes of the Persian kings on horseback shooting lions, arranged inside roundels bordered by series of circular form which are all Sasanian motifs, and against the background, the floral arabesques, still founded in the Persepolis in Shiraz, are arranged at the four corners of each roundel [21].

Sasanian goods, including silver, glass, brocades (Sasanian merchants imported the raw silk and woven into twills and brocades for export) and other items, decorated with Sasanian motifs, were carried east, and traded, along the ancient Silk Road, Sasanian motifs were adopted by Chinese craftsmen as ornamentation in wall painting, silk weaving, brocades and other local industries as is seen from a few extant pieces [9 in 5]. See examples in figure 8, the Sasanian motif of the goose or duck carrying a string of beads, on a jeweled pendant, a garland, or a sash in its beak and on other products such as silk and bowl. This motif appeared on quintessential Silk Road artifact, this silk textile is probably from a Chinese burial of a person of high rank (Figure 6. Left) and wall painting (Figure 7, in the wall paintings at Kizil, a Buddhist cave temple complex, along the caravan route skirting the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert) is decorated with a goose motif that is Sasanian motif in origin.

Figure 6. Left, Textile silk with Sasanian goose motif, Dunhuang area, China, circa 12th century. Right, Sasanian Territory

Figure 7. Wall painting with Sasanian motif, Xinjiang Province, 3rd to 8th cent.

Figure 8. Top-Left, A Pheasant as depicted in late Sasanian arts 6-7th Centuries. Top-Right, Sassanian silk fragment with peacocks, Aachen 6th Cent. Down, Drinking bowl, parcel-gilt silver, Sasanian 6th-7th century, the inside is engraved with a duck holding a ring or a necklace in its bill.

Figure 9. Sung Dynasty era, child’s silk jacket is in the Sasanian style.

Figure 10. Persia, Luristan bronze, 1st millennium B.C.

Figure 11. Chinese Product

Although Sasanian political control did not reach beyond the Pamir Mountains in Central Asia, the cultural influence of the Sasanian Empire (AD 224-651) extended far into East Asia (Figure 6.Right). The influence of Persian design is not only limited to the brocades which we see design of bronze products of Luristan (in Persia) related to the first millennium B.C. in Chinese Art (Figure 10 & 11) [5].

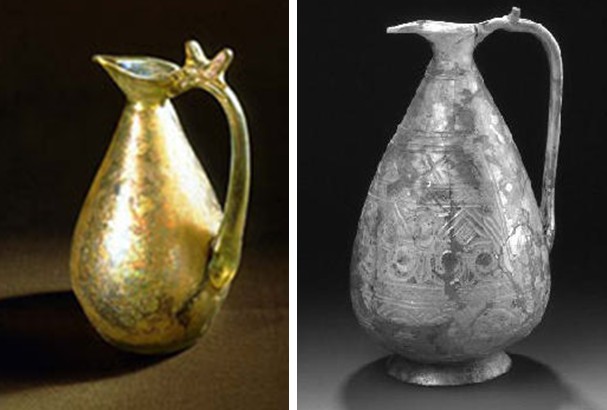

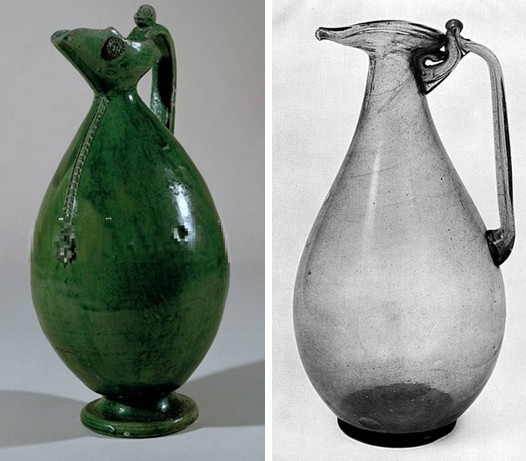

We see several Chinese conical jugs with pear-shaped body and handle with thumb-rest, with long cylindrical necks, the handle attached to a long neck and the main body expanding at the bottom which were imitations of Sasanian metal vase (Figure 12. Left) originated in the Persian Sasanian Dynasty (A.D. 226-642) [5 & 10].

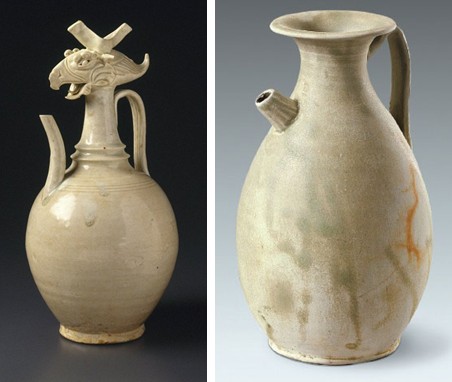

Another product is Dragon Headed Vase (Figure 14. Left) which the stately dragon's head forms the spout and its slender body which is extended as the handle. This magnificent object, combining a Chinese dragon and the Persian Pegasus- traditional motifs of east and west-conveys a sense of power and energy in design. This product is related to Asuka period although it had been thought to originate in Tang-dynasty (618-c. 907) China, but was inspired by gold and silver ewers from Sasanian Persia. In a similar product, we see Phoenix-Headed Ewer is a terrific example of "blue-white" high-fire ceramic (Figure 15. Left) which dates in the Tang Dynasty (A.D.618-907). Now we see many similarities between Chinese products and Persian designs, such as, products in Figure 12 and Post-Sasanian period jug (Figure 16. Right), circa 3rd-4th century AD. Also we see these similarities in the cast bronze ewer with pear form body, pedestal base, hemispherical mouth and handle with knops which on the rim of handle has shape like snake or dragon (like handle of 14 Right) with open mouth, and in another case, a cast Persian bronze jug, belong to Ghaznavid dynasty, circa 11th-12th century AD (Figure 16. Left) has conical base, handle with thumb-rest, the body with geometric and floral arabesques decorative pattern and the spout in the form of an ibex's head [11 & 12].

Figure 12. Left, Sasanian Vase, 6th cent. Right, Ewer with cut decoration. Persia, 9th cent.

Figure 13. Left, Jug, Tang Dynasty. Right, Eastern (Chinese) glass Jug with handle, 8th cent.

Figure 14. Left, Silver Dragon-Headed Vase, 7th century. Middle, Gilded silver ewer with dancing women; Sasanian period; 5th - 6th century A.D. Right, Sunken Ship, Tang dynasty.

Figure 15. Left, Phoenix-Headed Ewer. Right, Sunken Ship, Tang dynasty.

Figure 16. Left, Cast Persian bronze Zoomorphic ewer. Right, Post-Sasanian period, circa 3rd-4th century

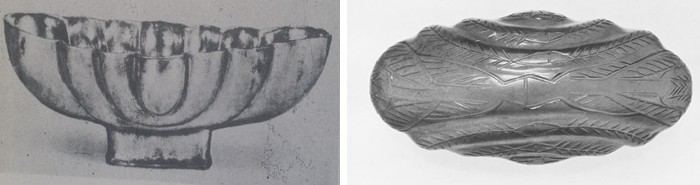

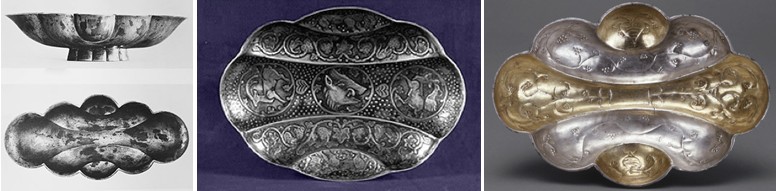

Figure 17. Left, Sasanian product . Right, Green glass lobed-cup, Sasanian, 7th century A.D.

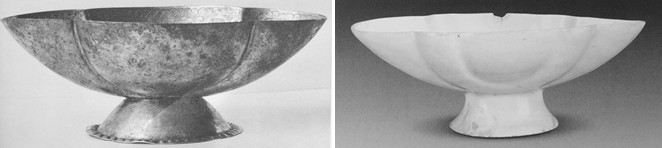

Figure 18. Lobed silver cups, Sasanian, 7th century A.D. [19]

Figure 19. Tang dynasty, 9th cent. A.D.

Figure 20. Left, Lobed elliptical silver footed dish, late Tang dynasty, 8th-9th century A.D., Right, ware lobed elliptical cup, excavated from the tomb of Qian Kuan dated to 900 A.D.

Figure 21. Changsha kiln products

The lobed shape cup is an engaging variation that appears and becomes popular in the arts and crafts of China, among the artworks some of the items are most noteworthy morphologically which are lobed products in figures 19, 20 & 21. Most of these eastern earthenware and metal utensils are from Tang dynasty; however, the distinctive vessels inspired from Sasanian and early post-Sasanian Persian products (Figures 17 & 18). The silver vessel (figure 18) as well as glassware of similar form (figure 17. Right), are during the Han dynasty which from the Persian Empire had reached China, a trickle that turned into a greater stream feeding the Tang Empire, which is still an important indication of the intercultural communication between East and Persia. Regarding to this communication F. H. Schafer says:

“ … Most of China’s overseas trade was through the south China Sea and Indian Ocean. From the seventh to the ninth century, the Indian Ocean was a safe and rich ocean, thronged with ships of every nationality… capital was moved to Baghdad at the head of the Persian Gulf, the eastern trade flourished greatly. Basra, an Arab city, was the port nearest to Baghdad, but it could not be reached by the largest ships. Below Basra, at the head of the Persian Gulf, was Ubullah, an old port of the Persian side of the Empire. But richest of all was Siraf, on the Persian side of the Persian Gulf below Shiraz. This town owed all its prosperity to the Eastern trade, and it dominated the Gulf until destroyed by an earthquake in 977. Its inhabitants were Persians in the main … The decline of Siraf was a disaster for the trade with the Far East …

From these ports, then, the ships of many nations set sail, manned by Persian-speaking crews –for Persian was the lingua franca of the Southern Seas, as Sogdian was the lingua franca of the roads of Central Asia. They stopped at Muscat in Oman … may be they risked the coastal ports of Sind haunted by pirates, or else proceeded directly to Malabar and thence to Ceylon … where they purchased Gems. From here the route was eastward to the Nicobars … then they made land on the Malay Peninsula … hence they cruised the Strait of Malacca towards the lands of gold … finally they turned north … to trade for silk damasks in Hanoi or Canton or even farther north.

The sea-going merchantmen which thronged the ports of China in Tang times were called by the Chinese, who were astonished at their size, (Argosies of the South Seas) … and especially (Persian Argosies) … the great ocean-going ships of China appear some centuries later, in Sung, Yuan and early Ming … when the Arab writers of the ninth and tenth centuries tell of Chinese vessels in the harbors of the Persian Gulf, they mean, ships engaged in the China trade…

… Chinese sources say the largest ships engaged in this rich trade came from Ceylon. They were 200 feet long and carried six or seven hundred men. Many of them towed lifeboats and were equipped with homing pigeons. The dhows built in the Persian Gulf were smaller, lateen-rigged.

(Canton was then the frontier town, during Tang a truly Chinese city) in the estuary before this colorful and insubstantial town were… the argosies of the Brahmans, the Persians and the Malays, their number beyond reckoning, all laden with aromatics, drugs and rare and precious things, their cargoes heaped like hills.

The Chinese taste for the exotic permeated every social class and every part of daily life: Persian, Indian and Turkish figures and decorations appeared on every kind of household objects. The vogue for foreign clothes, foreign food and foreign music was especially prevalent in the eighth century, but no part of Tang era was free from it.

Other exotic fashions of mid-Tang were leopard skin hats, worn by men, tight sleeves and fitted bodices in the Persian styles, worn by women along with pleated skirts and long stoles draped around the neck and even hair-styles and makeup of Un-Chinese character.

Dates had long been known as a Persian products and in Tang (‘s period) were actually imported.

Despite the excellence of the Tang textile industry or perhaps because of it … many clothes of foreign make were imported… therefore, the handsome Tang fabrics preserved in the Shosoin and Horyuji at Nara in Japan and the almost identical ones found near Turfan in Central Asia, display the popular images , design and symbols of Sasanian Persia…” [13 in 5].

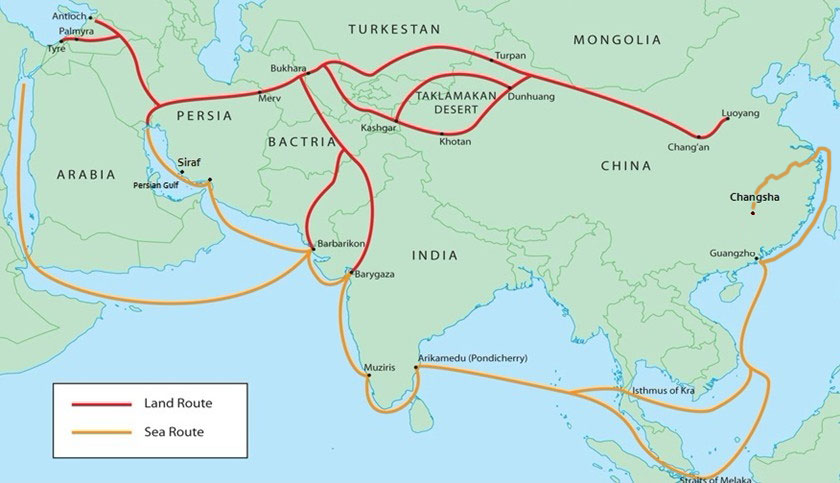

Figure 22. Map of silk roads.

In the first three hundred years after the Islamic conquest of Persia, China reached new heights under the Tang dynasty (618-905). Chinese improved commerce specially in the southern part of China, new patterns developed in poetry and painting, paper, potteries, printing and tea were discovered and academic institutions became so firmly established that they remained almost unchanged until 1912, (for example, As one of the four most prestigious academies in China, Yuelu Academy is a famous institution of higher learning as well as a centre of academic activities and upholding cultures since it was formally set up in the ninth year of the Kai Bao Reign of the Northern Song Dynasty (976). Yuelu Academy, surviving the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties, was converted into Hunan University in 1926).

Persia continued their relations with China. During the Tang Dynasty, communities of Persian-speaking merchants, known as Húrén(胡人), formed in northwestern China’s major trade centers. A large number of Central Asian and Persian soldiers, experts, and artisans were recruited by the Yuan Dynasty of China. Some of them, known as Sèmù rén (色目人) occupied important official posts in the Yuan Dynasty administration [14].

Therefore contribution of Persian and Chinese designers to a wide range of art, design and commerce disciplines is often overlooked. This paper provides a glimpse of the rich cultural heritage within the Persians and Chinese with significant role of both cultures that have played in the advancement of products.

2.Method

This context of understanding is not limited only to the above examples on trade of Persia and China, as we are sure there are more products which China has sent to Persia in period of Tang dynasty. In this study we have specified to look for Chinese products, especially here we have traced to explore Changsha wares (made by Changsha kiln) exported to Iran, which are similar to the discovered products of the Black Stone sunken ship in Tang Dynasty.

For this aim we used pictures of 100 products which have been discovered from the sunken ship, we used them as a base to find similar products in Iran.

3.Discussion

Historians have believed that thousands of wooden ships were traveling through the Maritime Silk Road between Persia China, which some of them have sunken there but time and the ocean have destroyed them. This has remained unknown until 1998 which a ninth-century shipwreck (named Black Stone) in the sea area of Indonesia was discovered, on which there were about 60,000 of well-preserved product and more than 80 percent of them were from Changsha Kiln ceramic products, since these products on the ship were obviously produced for the Persia in light of their exotic design styles. In this research we have become eager to find similar products of Changsha kiln in Iran, we have gone through the record of F. H. Schafer to find a location for our research and we found Siraf Port to just focus on which were the important and active port of Sasanian and Abbasid Dynasty in Persian Gulf [15].

Therefore we have collected related 100 pictures of product belong to the sunken ship which they were made by Changsha Kiln from Hunan province, the white porcelain kiln groups in northern China and the celadon kiln products in the south of China [12]. We had shown the pictures to experts who are working in the field of archeology in the Boshehr province.

After 6 months wide research we could find a good result with the help of Dr. Nasrollah Ebrahimi who has got his Ph.D. In field of “Historical eras” from Tehran University and is a faculty and researcher of Boshehr Organization of Cultural heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism.

They have found similar products of Black Stone shipwreck in Siraf. In report Dr. Ebrahimi says:

“Based on the discoveries of Siraf in the past and the pictures of discovered products of Black Stone shipwreck, I can identify following pictures of products (Figures 23, 24,…30), but unfortunately we have not found any complete product in Siraf in the past discoveries and just we could find pieces of broken part of products there. But based on the color and the technique of glazing clearly I am sure now the broken parts of following products are discovered in Siraf.

- Milky color wares.

- White and blue wares which has used blue cobalt in the patterns, which are also discovered in the city of Basra.

- Celadon wares with sprinkle green color glaze.

- Wares with brown glaze.

Based on our research the discovered broken wares are not similar with local pottery therefore they can be just imported products and the picture of Black Stone shipwreck is shown the same.”

Now, this result comes out from this report that:

-The broken wares with Milky color are related to porcelain kiln groups in northern China, and later to the south of China.

- The broken white and blue wares and wares with sprinkle green color glaze are related to the celadon kiln products in the south of China.

- The broken wares with brown glaze can be from Changsha Kiln from Hunan province.

Figure 23. Left, Blue and white porcelain dish of Tang Dynasty, which was found in the Blackstone Wreck Ship. Right. Xing Kiln porcelain, which was found in the Blackstone Wreck Ship.

Figure 24. Yue Kiln porcelain, which was found in the Blackstone Wreck Ship.

Figure 25. White glaze, green color porcelain, which was found in the Blackstone Wreck Ship.

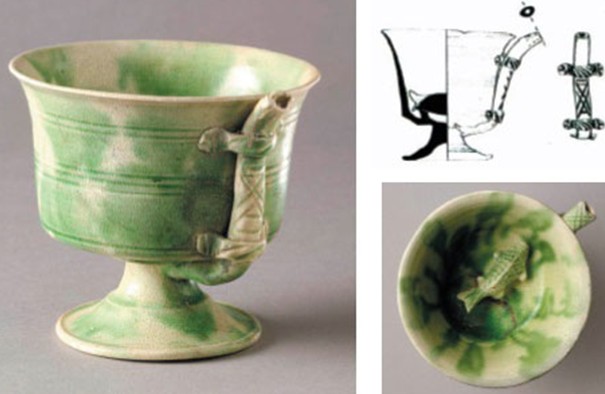

Figure 26. Left, Celadon glaze green-brown-color bowl of Capricorn pattern, Height: 6.4cm; caliber: 20cm. Capricorn is the transliteration of Sanskrit, which is one of the common animals of buddhism culture, and it has been regarded as the god of river water lives. The pattern of Capricorn almost takes the whole surface of the bowl, with rough brush strokes and vivid shape. Right, Celadon glaze green-brown-color bowl of Hu Ren portrait pattern (Hu Ren: the northern barbarian tribes in ancient China), Height: 6.4cm; caliber: 20cm, Drawing Hu Ren portrait on the surface of the bowl, which has thick curly hair covering his eyes. The big nose and rough figure are the significant features of Hu Ren.

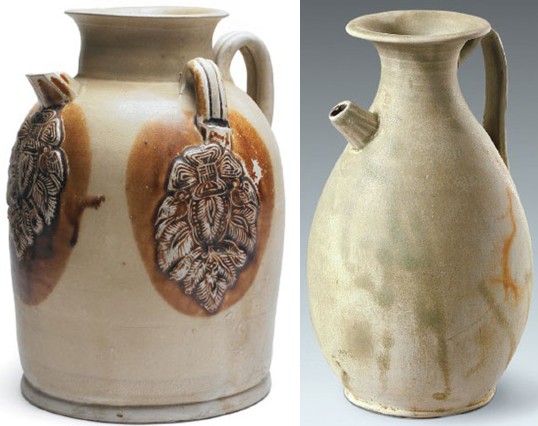

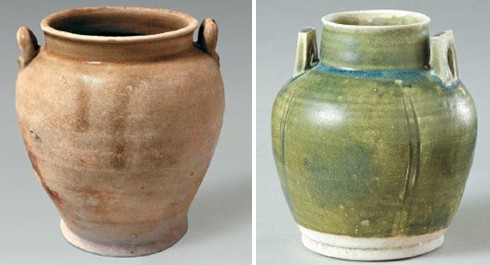

Figure 27. Left, Celadon glaze brown color flower pot of printing paste pattern, height: 23.5cm; caliber: 9.3cm. Bottom diameter: 16.5cm. This pot has horn mouth, outside lips, short neck, plump shoulders, multi-edge short export, curved handles, deep belly and flat base. There are some brown decoration patterns on the surface. This was frequently exported from Changsha Kiln. But it is the first time to unearth so many complete artifacts in one time. Right, Celadon glaze pot, Height: 21.5cm; caliber: 8.5cm; bottom diameter: 8.5cm; This pot has horn mouth, curved neck, multi-edge short export, curved handles, oval abdomen and flat bottom. The entire pot surface is covered with celadon glaze.

Figure 28. Left, Celadon glaze pot, Height: 13cm; caliber: 7cm; bottom diameter: 7cm. The bottle mouth is open, with short neck, double handles, and flat bottom. The entire surface is covered with yellow glaze. Right, Green glaze pot, Height: 17cm; caliber: 4.8cm; bottom diameter: 7.1cm. The bottle has straight mouth, short neck, square handles, four grooves on the surface and flat bottom. The entire surface is covered with green-blue glaze.

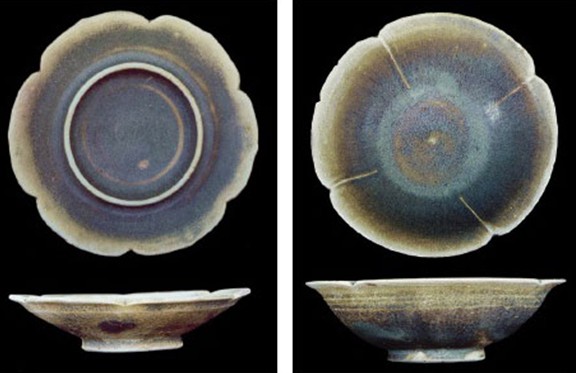

Figure 29. Left, Brown blue glaze lamp holder, Height: 2.6cm; caliber: 12.8cm, Open mouth, six petal lotus shape, round feet. The entire surface is covered with brown-blue glaze. Right, Brown blue glaze bowl, Height: 5cm; caliber: 14.3cm Open mouth, four petal lotus shape, four grooves on the surface, round feet. The entire surface is covered with brown-blue glaze.

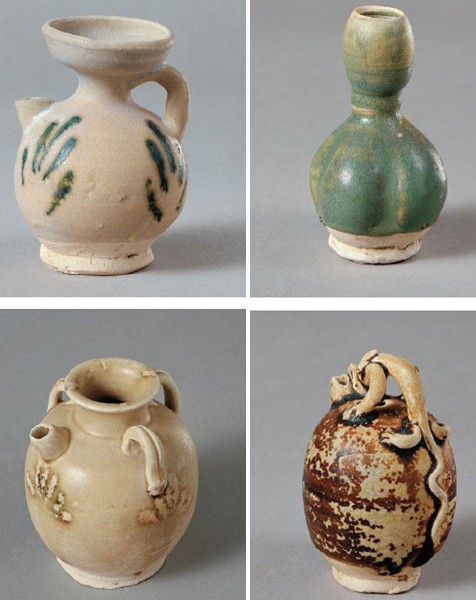

Figure 30. Left, Celadon glaze green-brown color water jet, Height: 9cm, Round body like a ball. Green bar-type decorations on the surface. And Celadon glaze green-brown color water jet, Height: 9cm, Horn mouth, plump shoulders, green plant-shaped decorations on the surface. Right, Green glaze green-brown color gourd-shape water jet, Height: 10.4cm, Gourd shape body with small mouth and two-layer neck. The surface is in green glaze. And Brown glaze dragon-shaped water jet, Height: 10.8cm, the handle is like a Chinese dragon. Combined with other parts, it looks like a whole product in harmony. No neck. The glaze on the surface is peeling.

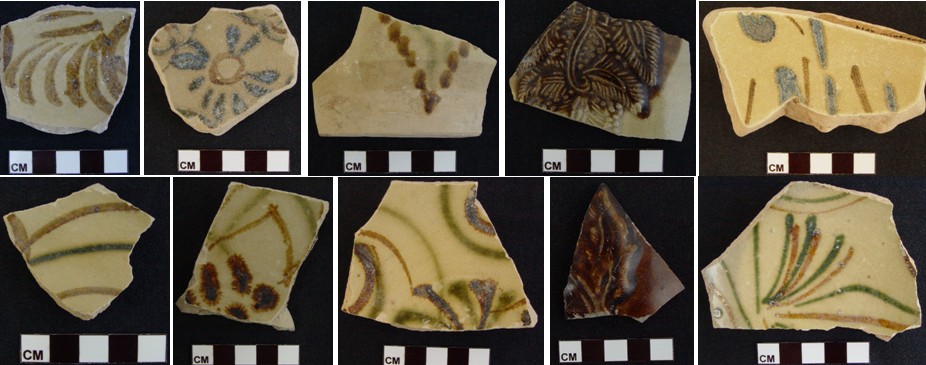

And also we found the Changsha Wares from Siraf in South of Iran, related to 8th Cent. (mid)-10th Cent, through the discovery of the British Museum (Figures 31, 32 & 33) which shows the huge export of Changsha kiln to Persia. For this discovery the British Museum Siraf Project has started in 2007 as a two years research initiative supported by the British Institute of Persian Studies. The aim of the project was to provide a complete catalogue of the excavated finds from Siraf in the British Museum. The collection of over 20,000 artifacts from Siraf represents one of the largest archaeological assemblages held by the Museum's Middle East department.

All of the finds and samples from Siraf in the British Museum are registered and entered on the Museum’s central database. These records form the basis of further research and analysis of the collection and serve as a primary record of the objects themselves. Specification, descriptions and images of the finds from Siraf can now be accessed by searching the Collection database online [16].

The information that has been recorded about the finds from Siraf is being brought together for publication as a British Institute of Persian Studies monograph.

Figure 31. Left, Copper alloy Chinese coin; South Iran, Bushire, Tahiri, Siraf. Meddle & Right, Song dynasty coins, South Iran, Bushire, Tahiri, Siraf. British Museum

Figure 32. Changsha Wares, South Iran, Bushire,

Tahiri, Siraf, 8thC(mid)-10thC, Fully reconstructed wheel-thrown pottery

bowl; low squared and bevelled foot-ring, curving sides and a simple

gently everted rim; covered with a white slip and translucent shiny

light green glaze over the interior and exterior stopping above the

foot; interior decorated with sparse abstract green swirling patterns;

underlying fabric is a fine buff colored borderline

earthenware/stoneware, British Museum

Figure 33. Broken Changsha Kiln Wares, 8th Cent.(mid)-10th Cent. , South Iran, Bushire, Tahiri, Siraf, Stoneware bowl rim sherd; wheel-made; covered with a buff-colored slip, painted decoration and a clear glaze, British Museum.

4 Conclusion

Here we have traced the historical perspective that influenced the development of aesthetics of product in both Persian and Chinese cultures, we have realized that the Persian products were exported to China in period of Sasanian and later the Changsha wares and northern and southern wares with same design of Sasanian were imported in Abbasid Dynasty. They include considerations involving visual elements and their inter-relations. For example, the product design (Figures 12Left, 14Middle & 17) went to China through the Silk Road in Sasanian period and the same design (Figures 15Right, 14Right & 21) were coming back to Persia with a little change in the Tang dynasty with Black Stone sunken ship.

This context of understanding is not limited only to the above examples on potteries, as there are probably more products having a similar underlying story like that of the relationship between erstwhile Persia and China. Therefore contribution of Persian and Chinese designers to a wide range of art, design and commerce disciplines is often overlooked. This paper provides a glimpse of the rich cultural heritage within the Persians and Chinese which both side have played in the advancement of product design. It presents the rich creativity of Persian and Chinese designers in periods of Sasanian and Tang Dynasty, traces the Persian art and Chinese regions and dynasties, highlighting their relationship from the inception until the present, which with this overview of the history between China and Iran, we find that frequent exchanges of culture, religion, trade, art, science and technology are the distinctive features of their bilateral relations. John W. Garver, Professor of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology, concluded that, China and Iran shaped their perceptions and power projection through cultural interactions and thus, paved the road for their cooperation and friendship [18]. In fact, this is also the contemporary history of friendly relations between accumulation and foundation [3].

References

[1] Burton, W.. (1961). Records of the Grand Historian of China. (trans of Shiji) New York: Columbia University Press.

[2] Feng T. (1996). Diplomatic History of China, Wuhan: Hubei People’s Publishing House.

[3] Liu, J. and Wu L. (2010) Key Issues in China-Iran Relations, Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia) Vol. 4, No. 1

[4] Nehru, J. L. (1934). Glimpses of World History. New Delhi: Penguin Books. P.188(1-8)

[5] Nasr, T. (1974) The Eternity of Iran, A publication of the Ministry of Culture and Arts.

[6] Wood, F. (2004). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[7] Ghirshman, R. pp. 212 to 256 in (1-115). Iliffe in the Leg. Of Pers. P. 26, (1-4).

[8] Laufer, B. (II-148)pp. 488, 512, 515 & 41- Also Kentok Hori, AChinese Account of Persia in the Sixth Century.

[9] Godard, A. Art de L’Iran, as quoted in Pers. Transl. of the Hist. of Persian Civilisation by J. Mohii.)

[10] Kroger, J. (1995) Nishapur: Glass of the Early Islamic Period, New York.

[11] Azari, A. (1988) History of Relation of Iran and China. Tehran: Amir Kabir Publication. ISBN: 964-00-0467-7

[12] Carswell, J. (1985) ‘Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World. Exhibition Catalogue.’ Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Gallery, University of Chicago, 1985

[13] Schafer, E. H. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarqand, University of Calif.

[14] Dillon, M. (1999). China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects, New York: Routledge.

[15] Glenister, R. (2009) ‘SECRETS OF TANG TREASURE SHIP: ABOUT’. National Geographic Channel. 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2011. http://natgeotv.com/asia/secrets-of-the-tang-treasure-ship/ accessed in May 2015.

[16]http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx?searchText=Siraf&page=1/ accessed in May 2015.

[18] Garver, J. (2007). China and Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-imperial World. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

[19]http://chinese-export-silver.com/meta-museum-archive/meta-museum-chinese-export-silver-19th-century-phenomenon-equivalent-ipad-%E4%B8%AD%E5%9C%8B%E5%87%BA%E5%8F%A3%E9%8A%80%E5%99%A8-%E5%8D%81%E4%B9%9D%E4%B8%96%E7%B4%80%E7%9A%84/ accessed in May 2015.

[20]http://www.kaikodo.com/index.php/exhibition_preview/detail/the_immortal_past/506/ accessed in May 2015.

[21] Encyclopaedia Iranica (2010) http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-index/ accessed in May

![]()

© 2015 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).